High jinks

- johannapoblete

- Jul 18, 2008

- 9 min read

Updated: Jan 31, 2023

Jumping off a Cessna 185 at 4,000 feet above ground level (AGL), and falling at an average rate of 200 feet per second (ft/sec) in free fall, and 12 ft/sec strapped to an open parachute, tends to slow things down. One looks at the sweeping panorama below one's feet and hopes one doesn't end up like Humpty Dumpty.

If truth be told, it could take longer to get on a plane and ready oneself for a jump than the actual jump itself. For one thing, one has to undergo a practical exam first (mandatory for a first jump and three months of skydiving inactivity). Also, the weather has to cooperate, with enough visibility for the tower to authorize a flight, the clouds remaining high above the drop zone and and not coming between the drop-off point and the ground, and the winds at ground level just 10 miles per hour (mph) to ensure the safety of neophyte jumpers (otherwise, the winds will literally blow us away).

We had meant to make the jump on Jan. 29—the day Downy challenged celebrities and the press to accept the capabilities of its newly launched "single-rinse" product or take a flying leap (at their expense)—but due to extreme winds, recurrent bad weather. variations in schedule, and miscommunication, we ended up making the jump on July 5 instead. Needless to say that the suspense (and expense!) was too much and by D-day, we were raring to go.

THE STALL

It was touch and go whether or not we were going to be able to make the jump on the day itself. There was a typhoon brewing north and the sky was overcast that morning, yet we made the two-hour road trip anyway to the privately run OMNI Aviation Complex at Clark Field, Angeles City. If the jump did get cancelled, the remaining five jumpers had already determined that it would not be for lack of motivation.

I was first to reach the airbase and discovered upon arrival that the pilots were grounded and no plane would be taking off until visibility got better. Mt. Arayat in the distance was obscured by nimbus clouds and thunder rumbled ominously in the background. At around 10 a.m. when the rest of the jumpers arrived, including three additions who had yet to be oriented (making the total count four men and four women), the sky still had not cleared and everyone was getting antsy.

To kill time, we sat in for the pre-jump orientation – not a small feat considering that we all suffered from information overload the last time. The better part of the day was spent in front of a white board, now and then checking if the weather had improved, while reviewing our physics and geometry like it was a matter of life and death, which probably isn't too far off the mark.

Calculating the probabilities of ground speed vs. air speed in relation to one's parachute (e.g., if the wind is 10 mph and the ground speed is 10 mph, then one rides at full glide at 20 mph) in a split-second was quite beyond my abilities. But knowing what was the expected action (e.g., when upwind from the target and being blown backwards, maintain a full glide) and reaction (don't pull on the brakes too suddenly, or all the way in a flare, else you stall in mid-air), was helpful. Plus there were air traffic rules to remember (e.g., always give the right of way to a lower parachute, and do not fly immediately below another's canopy and cause turbulence in your wake).

Martin Q. Imatong, our skydiving instructor, was adamant about letting us know exactly what we were getting into. Although he'd joke about crash-landing, he'd pepper his anecdotes with practical suggestions such as hanging on to an electrical wire with just one hand to avoid electrocution) should one stray into the line of posts, grabbing for that strong branch that can support one's weight when slamming into a tree, and avoiding the highway and runway at all costs, as there was no fallback option when faced with an oncoming vehicle

or plane.

Mr. Imatong is president of the Tropical Asia Parachute Center and holds a D-18848 license (expert) from the United States Parachute Association, with a rating of jumpmaster and instructor for tandem and static line jumps. He's logged in over 1,000 jumps himself, and been awarded Gold Wings 6351, Gold Freefall Badge 5092, and Falcon Freefall Award S248 BIC. He's also a member of the USA Pops 7667 and Parachute Industry Association (PIA), among other organizations. He had yet to meet a student who failed to take the jump or was injured. None of us were willing to be the first, and it should be said that confidence in the coach bolstered our spirits.

THE TEST

We finished up the lecture at around 3 p.m. and by then the sky had cleared enough to

give us hope. As part of the mandatory practical exam (taken after three months without a skydive), we took turns learning the footwork and positioning involved when making the

exit jump.

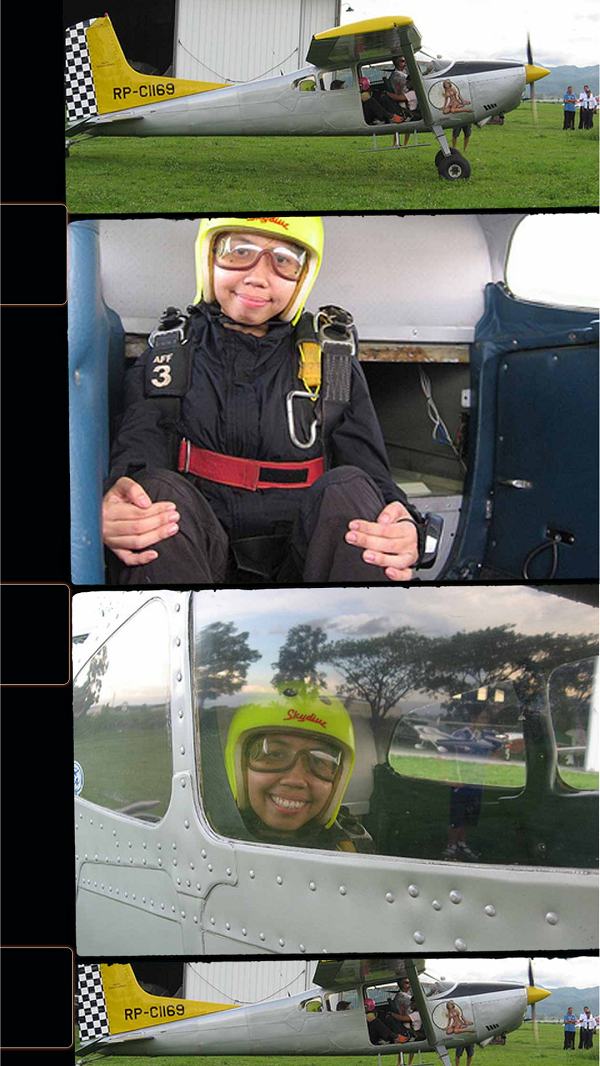

The Cessna 185 we used for practice was the same one we'd use during the actual jump as it had been modified for skydiving—the alternate pilot's chair and controls had been removed to make space for at least four jumpers, there was a gaping hole where the door should have been, and the floor was riddled with seatbelts and clasps.

Of the different ways to skydive, we were attempting the static line jump which entails a solo exit from the aircraft at a minimum height of 3,000 feet AGL and a solo descent under a parachute. The parachute is attached by a line to the plane which is then pulled (and thereby deployed) as the jumper falls away from the plane. From there, the jumper is able to control the parachute and independently determine how to approach the target landing point.

This type of skydiving is different from the instructor assisted deployment (IAD) where the instructor holds the pilot chute and controls the moment when the jumper's main canopy is deployed—but why burden the instructor when it's a simple matter to rig an automatic deployment using a line of rope and gravity?

Alternatively, accelerated free fall (AFF) can be made with two jumpmasters in tow who provide direct assistance during the exit and jump, but we didn't have enough people for that (and one has to wonder if it would be possible to process the instructions of two people screaming in one's ear while falling).

The third option was a tandem jump where a student jumper is attached to the front of the instructor's harness and is carried by him as a passenger throughout the jump, from exit to landing – not too fun for either as the instructor would be burdened with the entire balance and direction of the jump, while the student jumper has no control and will have nothing to do but mimic the instructor's positions.

Even knowing what to expect from the line jump we'd agreed to, we still needed to act out everything to the satisfaction of Mr. Imatong. After the exit drills at the plane, we also took turns being strapped onto a suspended harness to practice the initial freefall movements— arch for balance, look below to gauge where the target is, reach out to one's activation pin, pull for canopy deployment (not necessary for static line jump except when activating reserve parachute), and check upwards if it opens up completely—as well as miming steering and reacting to an emergency situation.

By the time we'd finished, it was already 5 p.m., and the men had to accept the fact that they wouldn't be making a jump that day, while the women suited up in a rush to beat sundown. In 15 minutes tops we'd zipped up, strapped on altimeters, pushed on goggles and helmets, and buckled in the parachute gear, and were marching like the astronauts from Armageddon to the air field. In five minutes, we were airborne.

And then the screaming and cussing started.

THE MOMENT OF TRUTH

The skydiving order is always the heaviest person jumps first and the lightest person last. Since I am an 87-lb. hobbit (at 5'1 ft.) strapped onto a 300 pound Manta 288 parachute, I'd been designated the last jumper. Watching the first of the jumpers fly off filled me with awe (I doubt I'd have had the guts to be the first lemming), and cheering the next two released some of the suspenseful tension.

I'd only caught a glimpse of their canopies, the wind snatching them away from the plane in moments, but it made me all the more determined to make my momma proud (if ever I do decide to tell her about this stunt). So I bore up, kissed my instructor on the cheek for luck, smiled when pilot William Wright gestured for me to wipe off my apprehensive frown, and took my place by the door.

Then I choked.

The world below was a a blur of blue and green and stubby little green balls that passed for trees, and flattish brownish squares that passed for houses. It was beautiful, it was scintillating, it was alienating, and the wind roaring to take me down to it scared me spitless.

I completely forgot my five-step strategy to exit the plane, and being obsessive, decided that I had to do it right or die. At which point, I screamed, "No! Wait! I don't remember!" in manner of incoherent Jim Carrey going bonkers in that movie Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

Mr. Imatong asked the plane to be turned around and verified whether I was still of sane mind and body and willing to launch both into airspace. Feeling the plane swerve out of position was a slap in the face, literally and metaphorically, so I sat down at the edge of the plane, with my feet dangling, my mind going into sharp focus and my body gearing up to jump. Any jump, perfection be damned. And while the internal battle was waged, my instructor's assurances that he believed in me and that he would help me added to the tumult. So when the cue came, I stood up, held on to the wing with my right hand and onto the door handle with my left hand. kept my feet firmly in the X position at the foot stand, and at the count of five, let go.

My memory of the first five seconds of the fall is hazy, but I was told by Mr. Imatong that I managed to execute a perfect arch—sheer blind luck combined with muscle memory—and that I'd showed him another way of making an exit (e.g., fellow hobbits in the future will benefit from my panic-driven balancing act).

What I do remember is looking up to see my canopy opening beautifully, a red and blue wonder that calmed me with its perfect spread, never mind the harness jerking me up by the thighs and shoulders.

I relaxed.

Speed became relative at this point—the airspeed relative to the speed at ground level and how this affects the speed at which the parachute moves through the mass of air—and I couldn't be bothered to make up sums in my head. The sheer wonder of being suspended over 3,000 feet above the ground according to my altimeter, was breathtaking in ways that weren't entirely dependent on bodily response to altitude. I tugged my toggles to half-brake, first to take my bearings, but kept them there simply to take in the view. I couldn't tell where the heck I was, exactly, saw no sign of the others, and I felt totally alone.

Everything seemed so still, I was waltzing on air, easily moving downwind. It was a peaceful, heady feeling.

Ok, I was high on hypoxia, Icarus before the glue fell to pieces.

A man's voice snapped me out of my momentary daze, barking out from the walkie-talkie strapped at my back, a far cry from the whispered "Welcome to the world of skydiving" that had barely registered a moment before. The sense of urgency in his tone made me reluctantly steer the parachute the way I had been taught, abandoning the stillness in favor of a concerted effort to find my way to a safe landing point.

In a few seconds, I had reached 1,000 ft. and voluntarily went on full glide, without being ordered to do so. I could identify where I was by then, north of the planes and the waiting cameras, and nearing the three mango trees that bordered the airfield. A few grapples with the toggles, and I'd cleared the trees and entered the Omni perimeter in my approach, swiftly meeting the ground and hearing my guardian barker insist that I flare. So I pulled fully on the brakes and landed safely—almost gracefully—into a butt-slide.

Slap-happy, I watched friends and photographers running to where I was. I could see where my fellow jumpers had gone to—and found out later that one was blown farther, into the heart of the brush, and the other two reached the edge of the highway and hitched a ride on a carabao-herder's motorcycle.

But in that moment, safe and still on the ground, I was still basking in the adrenaline rush and wondering if I would ever have the chance to chase the wind again and dance on air.

Originally published on 18-19 July 2008 as the main feature in BusinessWorld Weekender.